13 ноември, вторник

І. Лукиан. Луций или магарето

1. Фабула на романа. Особености на фабулата в сравнение с други романи

Героят, който се казва Луций и е родом от Патра, пътува за Тесалия, за да предаде писмо на един местен жител на име Хипарх. Намира дома на Хипарх и домакинът го поканва да остане. Из града среща позната заможна жена, която го предупреждава да се пази от жената на домакина си (1-4).

Флиртува със слугинята Палестра. Описание на нощните им забавления. Една вечер Палестра му показва как господарката й се превръща във врана. Луций също пожелава да се превърне в птица. Палестра погрешно го намазва с друга смес и го превръща в магаре. Уверява го, че това ще е за кратко, защото, за да стане обратно човек, е достатъчно да изяде няколко рози (5-14).

Луций, превърнат в магаре, прекарва нощта в яслата. Преди изгрев слънце в дома нахлуват разбойници, ограбват всичко и натоварват Луций с плячката. По пътя той узнава, че не може да говори, а само да реве; че все още предпочита човешка храна, а не магарешка; и че, независимо от променената си външност, е запазил разсъдъка и чувствата си.

Спират при един помагач на разбойниците, градинар, където Луций яде от зеленчуците. Градинарят го удря, Луций го ритва и след това е наказан с бой. По-късно мисли дали да не легне на пътя и да откаже да върви нататък с разбойниците. Другото магаре го изпреварва и прави точно това. Разбойниците прерязват сухожилията му, хвърлят го в крайпътна пропаст и разпределят товара му между Луций и коня. Накрая пристигат в постоянния си лагер, където ги посреща тяхната икономка - стара жена. Сядат да вечерят (15-20).

На другия ден разбойниците довеждат пленена млада жена. Говорят, че магарето е куцо и слабо, и че е по-добре да го убият. През нощта Луций успява да избяга с момичето на гърба и въпреки съпротивата на бабата-икономка. Разбойниците ги залавят и ги връщат обратно, където откриват, че бабата се е обесила. Намислят мъчителна смърт за Луций и момичето (21-25).

На сутринта в лагера нахлуват войници, избиват разбойниците и освобождават момичето и магарето. Момичето се връща при годеника си, от когото е било отнето. В началото за благодарност го изпращат в стадото на кобилите, но там е нахапан от жребците, а след това е даден да работи в мелница. После започва да пренася дърва под надзора на един жесток млад магаретар. Той го товари прекомерно, бие го и дори опитва да го подпали. Луций се спасява, като изгасява обхваналия го огън в една локва. Накрая магаретарят го наклеветява, че по пътя нападал младите жени по пътя и се опитвал да ги обладае. Слугите обмислят да го убият, но накрая решават, че е по-добре да го скопят. Луций се изплашва много (26-33).

Някой съобщава, че младата жена и съпругът й неочаквано се удавили. Робите разграбват имуществото и се разбягват; Луций е натоварен и пристига в македонския град Берое. Продават го евтино на група скитащи "жреци на Сирийската богиня". В един град след представлението си на площада те довеждат в квартирата си някакъв случаен младеж и започват да развратничат с него. Луций вдига шум, издава ги и става причина да ги изгонят от града. Те го набиват, но не го убиват, защото той носи статуята на богинята им (34-38).

Установяват се в къща на един богаташ, чийто готвач е допуснал кучета да изядат бут от диво магаре, който е трябвало да бъде поднесен на вечеря. Готвачът мисли за самоубийство, но жена му го съветва да убие Луций и да вземе неговия бут. Луций се преструва на бесен, затварят го, после продължават пътя си. В едно село жреците открадват от храма златна фиала; разкрити са и са хвърлени в затвора (39-41).

Луций е продаден на един мелничар, а после на беден зеленчукопродавец, при когото гладува. Стопанинът му се сбива с римски войник и се скрива, за да не бъде арестуван. Луций го издава по невнимание. После е продаден евтино на двама братя - роби на богат човек от Солун (42-46).

Стопаните му разполагат с много и вкусна храна, която той яде в тяхно отсъствие. Те узнават това, изненадват се и започват да го показват и на други хора; обучават го да се държи на трапезата като човек и се учудват на схватливостта му. Господарят им го вижда, харесва го и го отвежда в Солун, където много хора са любопитни да го видят. Така той заживява добре и с времето надебелява и се разхубавява. Една жена го пожелава и той става неин любовник (47-51).

Решават да го представят в театъра, където той да обладае жена, осъдена на смърт. Там случайно вижда венец от рози, изяжда го и се превръща отново в човек (52-54).

Публиката се смайва и го подозира в магьосничество. Той разказва цялата история, съобщава произхода си и е освободен. Среща се отново с местната си любовница, но тя го отхвърля с думите "Аз не теб, но магарето в теб обичах!" Напуска града с кораба на брат си и се прибира в родината (55).

2. Типови събития и герои. Новото в "Роман за магарето"

а. събития

б. герои

3. Литературни влияния, скрити препратки към и цитати от други антични съчинения

ІІ. Апулей. Златното магаре

1. Фабула на романа. Различия от Луций

2. Типови събития и герои. Различия от Луций

а. събития

б. герои

3. Приказката "Амур и Психея". Мистериите на египетските божества

4. Литературни влияния, скрити препратки към и цитати от други антични съчинения

ІІІ. Съвременни учени за "Романа за магарето"

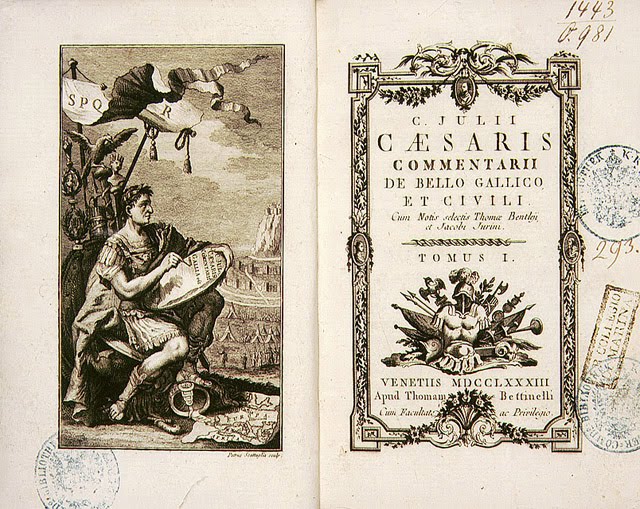

Apuleius was born at Madaurus in the province of Africa around 123 and was active at the second half of the century. Several works from his hand survive, including the Apologia, his self-defence on a charge of gaining his wife's love by the use of magic; but his fame rests above all on his novel the Metamorphoses, also known as The Golden Ass. This is based on a Greek tale, Lucius, or The Ass, possibly written by Lucian, of which an abridged version is still extant. Comparison with the Greek story serves to demonstrate how brilliantly Apuleius enlarged and adapted his model. The Golden Ass is in eleven books and is told in first person. After nearly three books of amorous and humorous incidents the narrator, as a consequence of an experiment with magic which goes wrong, finds himself transformed into a donkey; and the rest of the work consists of a series of picaresque adventures which befall the hero in his animal form, interrupted by a large number of other tales recounted by various of the characters who figure in the main narrative. The longest of these, the tale of Cupid and Psyche, occupies about a fifth of the entire work.

Finally, after a vision of the goddess Isis, the narrator Lucius is restored to his human shape. The last scenes of the novel provide one of the most remarkable accounts of religious experience to come down from classical paganism. It has often been thoght that we see here the influence of Christian spirituality; on this supposition Apuleius was fighting Christianity but doing his best to steal the rival religion's clothes. The last book also presents the interpreter of Apuleius with his most teasing problem; no entirely satisfactory explanation has yet been given, and perhaps none is possible. How are we to reconcile the tone of the conclusion, with Lucius as an adept of the goddess, vowed to celibacy and simplicity of life, with the huge gusto with which the rest of the story is told? Lucius repeatedly tells us that he is 'inquisitive', or 'a thirster after novelty'; for this inquisitiveness he is punished and ultimatedly redeemed, but until the last book the whole atmosphere and style of the narrative encourages us to rejoice and share in this thirst for adventure and experience... And entertainment is what we get, though often of a grotesque sort. Sex and magic, comedy and horror, elegant romance and coarse bawdy are blended into an intoxicating mixture;

Richard Jenkyns

Sex sells, as any publisher knows. That much was true in the second century too, though it seems a little magic and a lot of learning could be usefully added to the mix. Known formally as The Metamorphoses this is the only Latin novel to survive complete from the antiquity, and a remarkable piece of work it is…

So poor Lucius in his grotesque inhuman form is subjected to a series of misadventures that take him from one end of Greece to the other, and see him repeatedly stolen, sold, beaten, humiliated, owned by all kind of even more unpleasant characters and threatened by all kinds of even more unpleasant deaths, before eventually being scheduled for a performance in the arena in Corinth. His role is intended to be a central one, fitting to his, as is were, assets: he is to copulate with a woman condemned to death, and thus provide the instrument of her execution.

What was the purpose of such a scandalous composition? Apuleius himself explains in the prologue:

Now, in this Milesian style, I shall string various tales together for you, and caress your kindy ears with pleasurable murmurings…

Such tales got their name from Aristeides of Miletos, who, in about 100 BC, wrote a collection of saucy stories translated into Latin soon after by Sisenna. These originals have long sinse vanished, but their disreputable nature is commemorated in Plutarch's story that copies were found in the baggage of Roman officers (Life of Crassus)…

The question of the level of education that Apuleius expected in his readers is almost as important as the fun he provided them. The Metamorphoses is a work of the Roman literature that, as so often, is more than it pretends to be. It takes the form of a pseudo-biography, and in the last book Lucius, having finally found some roses while on his way to perform his terrible duties in the arena at Corinth, has resumed his human shape. What follows is an account, less racy but no less remarkable, of the hero's spiritual salvation through initiation into the mysteries of the goddess Isis. Those of contemporaries who knew about Apuleius' other interests might not have been all that surprised after all: he was also the author of a number of treatises on philosophy, such as On Plato and his Teaching and On Socrates' God. And of the very heart of the novel is a long tale that can hardly be called 'Milesian' at all, though it does share all kinds of elements with folk-tales from many cultures. It is told by an old crone to cheer up a pretty girl (obligatory in ancient novels, as in most modern ones) who has been kidnapped by a group of wicked bandits (obligatory in ancient novels though optional in modern ones). In this tale, a princess with the by no means insignificant name of 'Psyche' is offered up in sacrificial marriage to a mysterious monster whose identity she is sworn not to try to discover...

The tale is plainly a Platonic allegory of sorts, and, although scholars argue about its exact meaning, the experience of Psyche surely mirror and predict those of Lucius. Like Psyche, he is made to undergo a number of thoroughly dehumanizing trials to punish him for his impious curiosity, and like Psyche, too, he is eventually saved, not by his own merits, but by the intervention of a divine being whose power is matched only by her benevolence.

Michael Dewar

Библиография:

Апулей. Златното магаре. Превод Георги Батаклиев, Петър Радев. Народна култура, 1984.

Richard Jenkyns. Silver Latin Poetry and the Latin Novel. In: J. Boardman. J. Griffin, O. Murray ed. The Oxford History of the Roman World. Oxford UP, 1991.

Michael Dewar. Culture wars: Latin literature from the second century to the end of the classical era. In: Oliver Taplin ed. Literature of the Roman World. Oxford UP, 2000-2001.

About the Latin Academy in the Vatican

13 years ago

No comments:

Post a Comment